Sometimes even writers don’t know what’s going to happen next. When David Almond was working on the first draft of his multi-award winning debut novel, Skellig, he found himself surprised by the events unfolding before him as the lead character, Michael, discovers the strange creature of the title in the family garage.“He put his hands round Skellig’s back and I remember thinking bloody hell, he has got wings,” Almond says. It was only at that point that Almond realised the ‘creature’ was a fallen angel. “To my own astonishment,” he adds.

Ten years later, the Northumberland-based, Newcastle-born author was inspired by a similar sort of self-discovery to write the follow up, My Name is Mina. It came after he watched an impressive performance in the latest stage adaptation of the original novel [Sky TV also turned it into a film]. “Mina was being played by a fantastic young actor called Charlie Sanderson; I learned a lot speaking to her about what Mina was like,” Almond says.

“In Skellig, Mina had just jumped into the story fully formed. But watching her on stage I realised she must have had a troubled past and that a lot of her attitudes came from insecurity. She became someone I needed to know more about.

“Then when I sat down to write her it was almost as if she was there inside me saying ‘Aha! What took you so long? You’re here to write about me now!’”

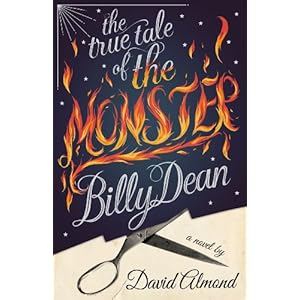

Something similar seems to have happened in the case of Almond’s latest and most challenging work, The True Tale Of The Monster Billy Dean. Almond’s writing has long appealed to both children and grown-ups readers, but this new work is arguably his most adult to date. This time, it was a voice which kept pestering him, demanding to be noticed: a voice that spoke in his own north of England accent, only more so. As Almond explains, it took him a long time to settle on writing the book.

“I knew I had this boy jabbering away in the back of my brain saying ‘write me, write me,’” he says. “And each time I sat down to write it I realised it would take a lot of time and energy to get it right and I knew I had to clear some space and time to get it properly. But it was the voice that did it. The language on the page had to match the voice I was hearing in my head.”

Billy’s story turned out to be a dark one – inspired, Almond admits, by real events: stories of children who had been hidden away by abusive adults. The author’s fascination for this subject runs deep, predating the recent case of the Austrian girl Natascha Kampusch.

“There is a Herzog film, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser [dating from 1974] about a boy kept in darkness for the first twenty years of his life. It had an enormous, shattering affect on me and I think since then I’ve been trying to write that movie,” he says.

“It is also very influenced by ‘the wild boy of Aveyron’, a true story of a French boy who grew up in the woods before they brought him out and tried to civilise him [he was discovered in 1797]. So it drew on those stories, people from the past who were brought up in darkness.

“There have always been stories about wolf children and kids who grew up with monkeys so it is using that idea but in what begins as a very ordinary northern town. You think: what will happen if these things happen there?”

.jpg/190px-Bradley_Manning_2_(cropped).jpg)