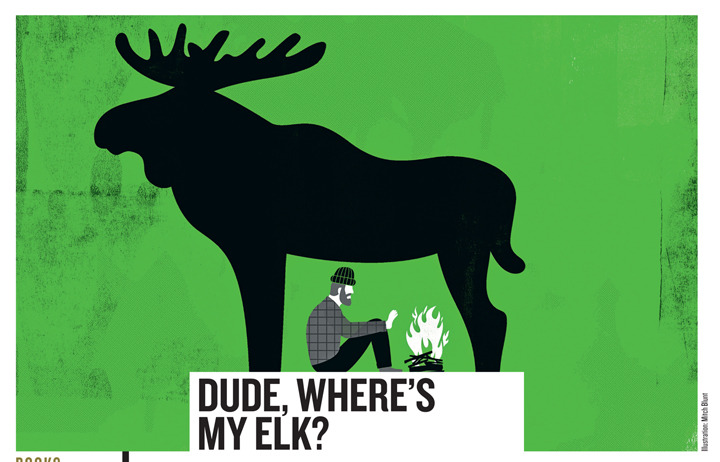

The cover of Doppler by

Erlend Loe comes with a neat little tagline: “An elk is for life... not just

for Christmas.”

John Lewis, eat your heart out. But clearly we are in

Norway, where elk roam free. I don’t know if you’ve ever been to Scandinavia

and seen one but a few years ago I drove past several while in Sweden and

marvelled at their big dopy faces, loping walk, and vast antlers. If the elk

was a Coen Brothers movie it would be

The

Big Lebowski.

Doppler is middle aged, his father has just died, and he’s

fallen off his bike. So he leaves his comfortable Oslo home, takes a tent and

heads off to live in the woods, “adopts” an elk calf and calls him Bongo.

He stays put for over a year, carves a totem pole and becomes

the focal point of an ad hoc all-male, tree-hugging cult. “The forest is gentle

and friendly,” he says at one point, like a Nordic Obi Wan. “It’s the sea which

is fickle. And the mountains. But the forest is predictable and less confusing

than almost every other place.”

The whole thing is funny and a touch dark. Norwegians seem

to have an endearing offbeat humour these days – the tone isn’t unlike Lillyhammer, the Steven Van Zandt comedy

BBC4 ran recently – perhaps due to being fabulously rich thanks to all their

oil. (Notably, this book’s satire dates from 2004, before the credit crunch,

austerity and the squeezed middle.)

It’s charming. And it made me think: Doppler’s decision to live

in a forest really isn’t so crazy. In fact, it is kind of extraordinary that

more men don’t follow his lead. That the woods aren’t stuffed full of middle-aged

IT workers, accountants and company directors who, like him, have grown fed up

of the routine drudge, their wives’ moods, and the sound of the Teletubbies on

TV. Men who only really want their own company. And to urinate in the open air.

Another short novel that caught my eye for entirely

different reasons was The Black Lake

by Hella S. Haase. A Dutch writer I’ve been meaning to introduce myself to for

a while, she writes about her country’s colonial history. She died in 2011 and

this novel actually dates back to 1948, but the translation is as fresh and as

current as any Booker nominee.

Haase’s young narrator grows up in Java in the 1920s and 30s,

his distant plantation owning parents a mystery, his only friend Oeroeg, the

native son of the estate’s foreman. As the boys get older they become aware of

the racial and cultural divisions which eventually will tear their world apart.

It’s barely a hundred pages but beautifully judged, and a genuinely intriguing

insight into the end of a European empire.

All of which has nothing whatsoever to do with tennis, the

subject of the first essay in Both Flesh

And Not by David Foster Wallace. You’ve heard of him: friend of Jonathan

Franzen; highly regarded in America’s literary circles; dead at 46, having

committed suicide following a long battle with depression.

These essays span two decades, and range from some thoughts

about Terminator 2 to a list of under

rated American novels. (Including Blood

Meridian by Cormac McCarthy, of which all he says is “Don’t even ask”.)

The most enjoyable is about watching Roger Federer play

tennis and dates from 2006, when the Swiss was at the height of his domination.

It manages to be detailed, strangely moving, and highly readable.

But no elks.

Doppler by Erlend

Loe (Head of Zeus, £7.99)